By Alex MacKinnon, fifth year student in Mining Engineering, and fan of transportation planning. If you would like to pitch us a guest post, get in touch–we’re a well-read forum for you to get your ideas out.

I’m sure the vast majority of people reading Insiders are pretty familiar with the transportation problems of the Broadway corridor. The viability of the status quo is frequently questioned. People ask why we need to do anything at all, why spend the money? Simply put Broadway will hit a point of diminishing returns on how many buses can be added and how many people can be moved cost effectively with buses. While the 44, 84 and 43 have been designed to partially take the load off the 99 there’s not much hope in those routes staying ahead of demand in the long term without large investments in improved service. Big infrastructure projects in Vancouver like rapid transit to UBC, have been put off for decades, but now it’s crunch time.

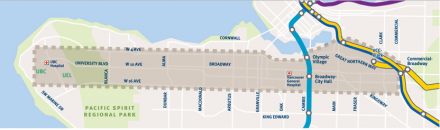

Translink and a number of stakeholder groups are currently carrying out the preliminary studies to judge future options on the Broadway corridor. There’s 3 main options on the table right now, each with a plethora of design options that need to be agreed upon in concept before things can really get moving forwards. Currently there are a lot of unsubstantiated arguments going around arguing one technology over another. I would like to try lay some of these arguments to rest and put forward a few of my own thoughts as to why we need more Skytrain.

The main contender in technologies to be used for the UBC line is skytrain. Since the system would be connected into the Millennium line there’s not much room for variation with the system design. It would be similar in train and station size to that of the Millennium line. The main factors in determining the cost of a potential system are the amounts of above and underground construction used as well as the length of line built. While the use of Skytrain can be considerably more expensive than any of the other options, the result is by far the fastest, most reliable and capacious of the options presented.

Light rail transit (LRT) is the second most popular contender which could be used on this project. LRT has by far the largest range of options available. It can range from streetcar running undivided from traffic all the way up to a fully grade separated system not entirely unlike our current skytrain system. The price of these options can range from tens of millions to a couple hundred million per km like Seattle’s LRT system. The speed, reliability and capacity of such a system would subsequently depend heavily on what options we choose.

The third contender for servicing the corridor is simply upgrading the existing bus service to a proper bus rapid transit (BRT) level of service. Like LRT this term is ambiguous in describing what degree of construction would occur in the project. The simplest and cheapest options are simply to remove a couple lanes of traffic, make them dedicated bus lanes and call it quits. Other options include lane separation (like what was used on No.3 Road in Richmond prior to the Canada Line), use of loading platforms with ticket vending machines, additional bus signal priority or even the use of larger 3 segment buses. Costs again will depend of how many of these capital projects get lumped into the upgrade and how many additional busses are purchased to meet demand.

The main arguments put forth for LRT are aimed at the low cost nature of a possible system. With this project you’re going to only get what you pay for, and even then it’s still going to be expensive. While it is possible to slap some rails on the street and run trains down the curb lane it would be very similar to our bus system in that the trains will be limited by their ability to get through a highly congested corridor. Even with a dedicated lane LRT or streetcar will only be able to boast an increased capacity per train over a standard B-line bus and a smoother ride. With signal priority added into the scenario LRT could move much quicker but the system would still not be consequence free for cross traffic. While the likely costs of a LRT system wouldn’t be as a large that of a Skytrain line, systems such as Calgary’s west-LRT expansion indicates that any decent LRT system would likely be over $1 billion.

The biggest caveat with running such a high capacity LRT system at grade down Broadway would be the inevitable traffic chaos that the system could incite. If we assume that eventually a hundred thousand people a day could be riding this system (which may be a low estimate given the Canada Line), a train would to have to run roughly every 2 minutes in each direction to meet demand due to limits on train length. Assuming that these trains were to receive signal priority at every intersection, every major intersection on Broadway would have to cycle about once a minute to let a train through. This includes Clark, Fraser, Kingsway, Main, Cambie, Oak, Hemlock, Fir, Burrard and Arbutus. Additionally due to corridor width restrictions it’s likely that all on street parking on Broadway would have to be removed, that sidewalks would have to be narrowed, and that left turns would have to be reduced to just a handful of intersections. To say the least this would make crossing Broadway a lot harder and greatly increase the amount of congestion on Broadway itself.

Many transit users are interested in LRT mainly because it would be a more usable option for people looking to get around their immediate community. Businesses also jumped at this point because it allows easier viewing and access to stores which may be located in between Skytrain or express service stops. The problem with adding in stops every couple hundred meters is that even the fastest trains or buses used in a local configuration will likely take longer than the existing service, therefore decreasing the number of people the service is attractive to and reducing the overall benefit which we can take from this project. If the new service doesn’t attract as many riders there is obviously less justification behind increases in overall density on Broadway, ironically resulting in fewer long term customers for the businesses on the Broadway corridor. While the LRT would produce a different streetscape and feel than a Skytrain based system these points seem to largely be driven by a fear of Canada Line style construction and people fearing changes in local trolley service.

Most people who are gun-shy about breaking ground on the new Skytrain line are either suffering from Canada Line syndrome where fear of large construction projects paralyzes development, or are simply unsure of the cost effectiveness of doing a full Skytrain build-out. While these concerns are valid we should be looking at ways of getting around these pitfalls rather than stopping dead before them. If construction started off as a tunnel bore leaving from the Finning lands heading west construction could be effectively phased. Over several years the tunnel could link up subsequent stations one at a time, opening each as a successive extension of the Millennium Line. While not as glamorous or speedy as the Canada Line’s build up this type of strategy would provide additional short term benefits while allowing additional construction to occur as finances and public opinion dictate.

Unlike the construction of LRT, the construction of a UBC Skytrain line wouldn’t be starting off with a clean slate. The operations and maintenance facilities for the line will likely already be in place before the first shovels hit the ground due to expandability likely to be built into the Evergreen Line extra. The benefits of the UBC Line expansion will be felt system wide, bringing additional benefits of scale and usability to the entire system. With the addition of the Evergreen Line and UBC Line the Skytrain system is going to be a relatively large transit system.

Vancouver is a city that has never done a good job building large infrastructure projects. Vancouver is a city built on the transportation industry which also bills it self as “world class” every chance it gets. This being said it seems laughable that large sections of what should be the backbone of our city’s infrastructure are missing. This city needs a full scale transportation system that can be counted on to provide fast, efficient and cheap travel for decades to come. While LRT could have any number of excellent uses throughout Metro Vancouver, the Broadway corridor isn’t a place where its qualities will shine. We need to dive in head first and go straight for the heavy rail.

How much is the “Skytrain lobby” paying you to write this?

P.S. This is an inside joke amongst those of us who support the M-Line being extended to UBC.

Skytrain is officially not classified as heavy rail, but as an intermediate light rail rapid transit system. Heavy rail means high capacity trains like Toronto, New York, Montreal…

“This city needs a full scale transportation system that can be counted on to provide fast, efficient and cheap travel for decades to come.”

They’re already building it, it’s called Gateway.

Gordon Campbell has stacked Translink executives with his friends and noted supporters. There’s no doubt in my mind that they’ll lobby to shove it in there. Broadway corridor residents are very NIMBY and will oppose. Besides, there’s not really anywhere to put it. Below ground is more expensive and makes the land more susceptible to failure during an earthquake.

I’m hoping Translink goes for streetcars: they’re exponentially less expensive, just as reliable and just as fast as the Skytrain.

World class doesn’t necessarily mean “spends the most”

Streetcars are pretty sexy, I agree. But, they don’t have anywhere near the advantages of skytrain.

The biggest advantage, and one that’s glossed over in this post, is the lack of a driver. Without a driver, you can have a significantly more frequency AND expanded hours of service for cheap.

One of the things that seriously separates Skytrain from regular, driver operated, light rail is that you can just run more trains. Look at Edmonton or Calgary, were in off peak hours, the wait between trains is often more than 15 minutes, where in Vancouver, it’s never more than 12, and usually at most 9. This is a big deal for accessibility AND capacity. Drivers are expensive, and you need to have a small army of them to run a streetcar at the capacity levels we need.

Because you have no driver, and the system is automated, your able to have more trains, and at a greater amount of hours, for super cheap.

Long term, skytrain is the best way to go, it pays for itself over time.

Mr. Haack: while you have the right to your own opinion, you do not have the right to your own facts. This–”streetcars…[are] exponentially less expensive, just as reliable and just as fast as the Skytrain”–is simply not true.

A streetcar along Broadway from Commercial to UBC would be no faster than the 99 B-Line and much slower and less reliable than the Skytrain.

What’s the point of a streetcar down broadway? Don’t we have that right now? The only difference is that they have rubber tires.

Chris:

For all intensive purposes Skytrain and heavy rail are pretty much the same thing. The Canada Line is considered heavy rail by most definitions, but Skytrain isn’t. I’d say this largely due to train width and a couple mechanical destinctions, which is a pretty arbitrary measure considering the number of things that they have in common.

Also while Gateway gets a lot of infrastructure built in a short time it doesn’t do much for Vancouver proper. I’d say as far as infrastructure goes, Vancouver should have the additional equivalent capacity of at least one of the east west freeways initially planned for the city in the pre 1970s freeway plan. While I don’t care to see a freeway built on 4th or 16th like those plans wanted, it would be nice if there was some form of infrastructure replacing that capacity.

Michael:

I think what a lot of people are overlooking when they say we should build a streetcar is that a huge amount of the road capacity is going to be sacrificed on Broadway if we run a decent street car system. If we hit skytrain like frequency with street cars, something to the effect of 30-40% of the cross broadway street capacity will be removed (I dont have my excel sheet on me right now).

Additionally if you think a street car can match the speed and reliability of a skytrain you out of your mind. Prof. Patrick Condon’s oft quoted 15M/km system is simply the Portland Streetcar. This street car has an average speed of 15km/h. Marginally faster than a 9 or 17. For reference the existing B Line can average up to 24km/h. A skytrain would likely average 35 km/h.

To put into perspective how quick the skytrain system is, we’ve got the highest average speed of any subway/metro system in North America.

Reliability is another big downside of street cars. To ignore the potential for crashes is pretty poor practice. For Instance the Houston LRT has had over 60 accidents in a year, with less than the expected ridership of a Broadway street car. Would you really consider a system which hits a car one in every 6 days reliable?

If you guys want to get into more detailed discussion I’d be happy to. My initial article resembled more of a engineering feasibility study than a blog post.

“Below ground is more expensive and makes the land more susceptible to failure during an earthquake. ”

Yest, tunneling is more expensive, but well-built tunnels can survive an earthquake. The magnitude 7.1 earthquake that struck the Bay Area in 1989 left the Marina District area on fire, collapsed sections of the Cypress Freeway in Oakland, damaged the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and the Embarcadero Freeway & Central Freeway were so severely damaged that they were later demolished.

The BART rail system, used by commuters between the East Bay and San Francisco via the Transbay Tube, was virtually undamaged and only closed for post-earthquake inspection. There was a train in the tube that automatically halted when the seismic alarms went off, and was sitting in the Transbay Tube under the bay for the duration of the earthquake. With no apparent damage, it was allowed to slowly continue to the nearest subway station to offload its passengers.

“For all intensive purposes Skytrain and heavy rail are pretty much the same thing. The Canada Line is considered heavy rail by most definitions, but Skytrain isn’t. I’d say this largely due to train width and a couple mechanical distinctions, which is a pretty arbitrary measure considering the number of things that they have in common.”

Again, this is not the case. Track width does not necessarily define ‘heavy rail status’.

Taken from Bombardier:

“Our Advanced Rapid Transit (ART) solutions fill the gap between street-running trams (low capacity) and heavy rail metros (high capacity). ART excels as a medium capacity transit system on dedicated guideways, whether at-grade, elevated or underground.” – Skytrain

Taken from Hyundai Rotem:

“LRV is a new urban traffic method suitable for mid-scale transportation between subways and buses. The high-tech LRV is an environmentally friendly transportation method, as it does not cause smoke or noise pollution.” – Canada Line

Skytrain and Canada Line are nowhere near heavy rail. I wish you would please learn up on the proper definitions.

“Heavy rapid transit trains might have six to twelve cars, while lighter systems may use only three or four cars. Cars have a capacity of 100 to 150, varying with the seated to standing ratio—more standing gives higher capacity.”

“A heavy rail system is an electric railway with the capacity to handle a heavy volume of traffic.[1] The term is often used to distinguish it from light rail systems, which usually handle a smaller volume of passengers.”

As much as I’d love to argue about what a dictionary says, this really isn’t advancing either arguement very quickly. Got a meaningful contribution?

It seems to me there are two problems with the current transit system. One is capacity, and the second is speed. People coming in from Burnaby on the 99 have a LONG commute, but for people living in Vancouver (and on campus), the big problem is capacity – 45 minutes is only an intolerable commute when your face is in some guy’s armpit.

If the problem is primarily capacity, why not run LRT down a number of east-west streets, (4th, 16th, 25th, 41st, etc), and divide the traffic. That would relieve some of the pressure off of the B-line, and help the overcrowding problem.

The big advantage of LRT is that it can carry a LOT more people than busses, and more comfortably. Many people would walk to a 16th street LRT, rather than take the B-line, even if it meant a few more minutes in transit (it probably wouldn’t). Or you could run the LRT down broadway, and an express bus down another street.

This would solve the capacity problem, and would help the speed problem. In the end though, it simply doesn’t make financial sense to build a 2 billion skytrain, when the only people who really NEED that option are Burnaby-UBC commuters.

Just FYI, when I say LRT above, I mean a streetcar-style LRT.

I would say that it would be a good step after a proper back bone is in place and if ridership can support it. The big downside is that if we split the system up into a few cheap branches we’re still going to end up with a system thats likely to be slower than an express bus and probably won’t draw as many people due to this fact. A cheap street car is simply bus++ unless you already have a good right of way.

King Ed and the west end of 16th could be a good place to run an LRT due to the wide median that was clearly placed with this in mind. Running a train down 41st on the other hand would likely be a pain in the ass as the right of way going through Kerrisdale isn’t very big.

When it comes down to it though, there still wouldn’t be as good of an excuse as with fully built skytrain line to plop a whole bunch of decent sized developments down on Broadway. I think you’ll find you get a lot more NIMBYs the farther you get away from the semi-dense areas of Vancouver.

Another way to look at this line is by addressing who you want to benefit from it. If you want to address the entirety of Metro Vancouver which is linked into the transit backbone and open up a big chunk of Vancouver to a greater variety of regional commuters then you really want to make sure that you’re addressing speed as well as capacity issues.

The vast majority of growth around Vancouver is projected to occur outside of CoV proper, Burnaby and Surrey are expected to grow by 75% in 30 years, while Vancouver is only slated to grow by ~15%. By then its expected that Surrey and Vancouver will have the same population. I think making sure the Broadway business corridor is accessible as possible to the entire metro area should be one of the core tenets built into this project. Broadway is still the 2nd largest employment area in Metro Vancouver, and that’s not projected to change. With the rise of Surrey’s urban core you’re also not going to want to isolate yourself from what could potentially be another large employment centre.

Alex, I have to agree with Chris on the “heavy” rail distinction. It might seem a moot point if looking at Vancouver in an isolated fashion, but in global terms Vancouver’s rapid transit system is very much lodged in an “intermediate” ranking for grade-separated “medium” capacity rapid transit.

Taibei’s MRT system, for example, has high-capacity trains < that absolutely dwarfs anything here, but also has a med-capacity line that looks and feels rather like our Skytrain

Why does this distinction matter? Any system that wishes to grow into the 2nd half of this century needs to consider how a future with double the population and a carbon constrained economy is going to absorb a tripling of transit riders. That means planning for our current needs (medium capacity) while leaving enough flexibility for a future high-capacity system.

In my opinion its mostly how the right of way is used and what kind of capacity you could throw onto it that makes the largest difference in what I think is heavy and what would be intermediate or light. Right now you could conceivably run the current skytrain system at 24000pphpd. It wouldn’t take much to bump this figure up to 36000 pphpd. Only an expansion of the station platform length, some more cars and a couple upgraded electrical substations. I can’t see those to factors making much of a change in my opinion of the overall classification of the system.