A historical polemic by UBC alum Mike Thicke

Do you know who the man in this picture is? If not, you probably lack a lot of knowledge that would be helpful in understanding the current activist climate at UBC. With Trek Park, the “Lougheed Affair”, and the recent Knoll Aid 2.0 RCMP confrontation, tension within the AMS has risen beyond reason. I think much of this tension is due to radically different perceptions of politics, history, and the role of student activists in society. While I can’t expect to convince SDS-UBC and The Knoll’s most strident critics of their value, I do hope that history can help us to find some common understanding and lead to more constructive dialogue.

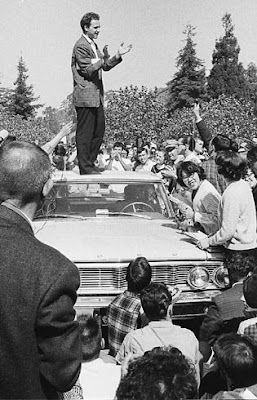

Do you know who the man in this picture is? If not, you probably lack a lot of knowledge that would be helpful in understanding the current activist climate at UBC. With Trek Park, the “Lougheed Affair”, and the recent Knoll Aid 2.0 RCMP confrontation, tension within the AMS has risen beyond reason. I think much of this tension is due to radically different perceptions of politics, history, and the role of student activists in society. While I can’t expect to convince SDS-UBC and The Knoll’s most strident critics of their value, I do hope that history can help us to find some common understanding and lead to more constructive dialogue. The man in the above picture is Mario Savio, the most prominent student leader at UC Berkeley (and in America) during the 1960s. He is standing on a police car. Inside the police car is Jack Weinberg, an activist and former Berkeley graduate student. In September 1964 the Berkeley administration had decreed that students on campus would not be allowed to promote political or civil rights causes through fundraising, passing out pamphlets, tabling, or other means. At the beginning of October, Weinberg was tabling for a civil rights organization, the Congress of Racial Equity. The police asked him for I.D., he refused, and they arrested him. A host of sympathetic students then surrounded the police car with Weinberg inside it, and did not move for over a day, at one point repelling an attempt by police to reach the vehicle. By the following evening, the students had negotiated with the university administration an accommodation for political activity on a portion of the campus, and the waiving of charges against Weinberg.

If student movements for change are rarities still on the campus scene, what is commonplace there? The real campus, the familiar campus, is a place of private people, engaged in their notorious “inner emigration.” It is a place of commitment to business-as-usual, getting ahead, playing it cool. It is a place of mass affirmation of the Twist, but mass reluctance toward the controversial public stance. Rules are accepted as “inevitable”, bureaucracy as “just circumstances”, irrelevance as “scholarship”, selflessness as “martyrdom”, politics as “just another way to make people, and an unprofitable one, too.”…. Tragically, the university could serve as a significant source of social criticism and an initiator of new modes and molders of attitudes. But the actual intellectual effect of the college experience is hardly distinguishable from that of any other communications channel — say, a television set — passing on the stock truths of the day. Students leave college somewhat more “tolerant” than when they arrived, but basically unchallenged in their values and political orientations. With administrators ordering the institutions, and faculty the curriculum, the student learns by his isolation to accept elite rule within the university, which prepares him to accept later forms of minority control. The real function of the educational system — as opposed to its more rhetorical function of “searching for truth” — is to impart the key information and styles that will help the student get by, modestly but comfortably, in the big society beyond. These are paragraphs that I feel are even more apt today (maybe substituting “Guitar Hero” for “the Twist”) than they were fifty years ago.

As Students for a Democratic Society, we want to remake a movement – a young left where our struggles can build and sustain a society of justice-making, solidarity, equality, peace and freedom. This demands a broad-based, deep-rooted, and revolutionary transformation of our society. It demands that we build on movements that have come before, and alongside other people’s struggles and movements for liberation. Together, we affirm that another world is possible: A world beyond oppression, beyond domination, beyond war and empire. A world where people have power over their own lives. We believe we stand on the cusp of something new in our generation. We have the potential to take action, organize, and relate to other movements in ways that many of us have never seen before. Something new is also happening in our society: the organized Left, after decades of decline and crisis, is reinventing itself. People in many places and communities are building movements committed to long-haul, revolutionary change. SDS-UBC was formed out of discussions last year about how to recover from the bitter decline of the Social Justice Centre. We felt that a new direction under a new banner was necessary, and the resurgent SDS offered both an inspiring legacy and strong allies. Members of SDS-UBC traveled this spring to an SDS conference in Washington State.  How about this picture? This is a community garden being planted in Berkeley’s People’s Park in 1969. People’s Park was built on land owned by the university originally intended for student housing but left to deteriorate after development plans changed. In April 1969 a number of community members began constructing a park on the land, without the university’s blessing. The park lasted for a month before police moved in to dismantle it under the direction of newly elected governor Ronald Reagan. The ensuing conflict resulted in the death of James Rector, shot by police while sitting on the roof of a nearby cinema. Today People’s Park is a Berkeley landmark.

How about this picture? This is a community garden being planted in Berkeley’s People’s Park in 1969. People’s Park was built on land owned by the university originally intended for student housing but left to deteriorate after development plans changed. In April 1969 a number of community members began constructing a park on the land, without the university’s blessing. The park lasted for a month before police moved in to dismantle it under the direction of newly elected governor Ronald Reagan. The ensuing conflict resulted in the death of James Rector, shot by police while sitting on the roof of a nearby cinema. Today People’s Park is a Berkeley landmark.

As the Vietnam was a catalyst for many far-ranging social changes in the 60s, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have given new life to activist movements around the world. Students across the US have formed the “new SDS”, declaring

Discussion

Comments are disallowed for this post.

Comments are closed.